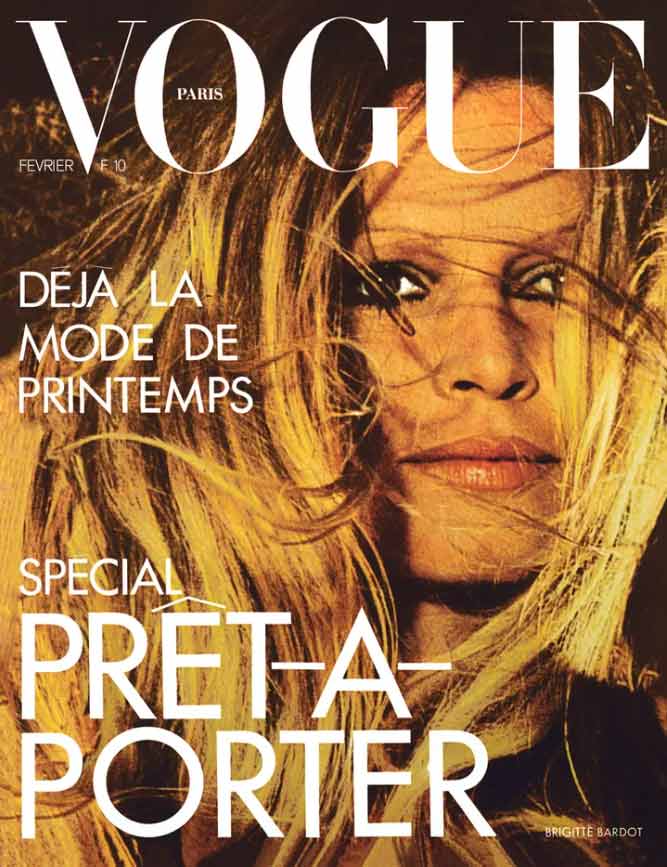

Can a cultural icon be disentangled from the political and moral positions she ultimately chose to embrace? With the death of Brigitte Bardot, France finds itself confronting that uncomfortable question once again, caught between nostalgia, denial, and a growing awareness of how celebrity can drift into ideological toxicity.

Can a cultural icon be disentangled from the political and moral positions she ultimately chose to embrace? With the death of Brigitte Bardot, France finds itself confronting that uncomfortable question once again, caught between nostalgia, denial, and a growing awareness of how celebrity can drift into ideological toxicity.

It is difficult today to listen to the uninterrupted hum of French rolling news channels without a lingering sense of discomfort. Since Bardot, universally known as “BB”, withdrew from acting under the banner of animal rights advocacy, what gradually emerged was not merely a retired star devoting herself to a cause, but a public figure increasingly defined by far-right views, racist rhetoric, and open homophobia. These positions, once dismissed as eccentric outbursts from a fading celebrity, found an unsettling resonance in a French society that has steadily shifted rightward, a drift mirrored, and at times reinforced, by a government whose policies and language increasingly normalize exclusion and repression.

Yet history resists simplification. In the haze of controversy surrounding Bardot’s later life, it would be intellectually dishonest to erase what once made her a defining figure of postwar European cinema. She was never a great actress in the classical sense. Rather, she was an icon, someone who understood image instinctively and mastered it completely. Her performances were often limited, even awkward, but those very limitations aligned perfectly with the aesthetic ambitions of a generation of filmmakers who rejected theatricality in favor of raw presence.

This is where the French New Wave enters the story.

Directors associated with La Nouvelle Vague, and those operating on its margins, were not searching for actresses who performed emotion; they sought bodies, faces, and silences that could exist onscreen without mediation. Bardot’s most emblematic contribution to this cinematic revolution remains Jean-Luc Godard’s Le Mépris (Contempt, 1963), a film that deliberately uses her body, her image, and her perceived emptiness as both subject and critique. Bardot also appeared in works closely aligned with the movement’s spirit, including Vie privée (A Very Private Affair, 1962) by Louis Malle, La Vérité (The Truth, 1960) by Henri-Georges Clouzot, often cited as a bridge between classical cinema and New Wave sensibilities, and earlier films such as Et Dieu… créa la femme (And God Created Woman, 1956) by Roger Vadim, which, while predating the movement, laid much of its cultural groundwork.

These films did not merely showcase Bardot; they used her. She became a canvas upon which male directors projected anxieties about consumerism, desire, fame, and the commodification of women. The New Wave, often accused of elitism, generated an entire industry of commentary, allowing critics and journalists to produce endless theoretical exegesis. Bardot stood at the center of this discourse, less as an artist than as a symbol.

The most tragic arc of Bardot’s life, however, lies in her transformation. She moved from being a hyper-sexualized emblem of cinematic liberation to an embittered, abrasive figurehead of the French far right, provocative, insulting, and increasingly aligned with extremist factions within the animal rights movement. Her rhetoric grew harsher with age, her provocations more calculated, her public interventions less defensible.

A woman of excess in every sense, Bardot also made a brief foray into music, notably collaborating with Serge Gainsbourg on songs such as Initials B.B. and Bonnie and Clyde. Like much of her career, it was glittering, ephemeral, and ultimately of limited artistic substance, yet perfectly illustrative of a cultural moment dominated by spectacle, celebrity, and controlled scandal.

It is difficult to imagine Brigitte Bardot’s global notoriety without the French New Wave and its satellite movements. Without that cinematic rupture, she might well have faded into obscurity. But history chose otherwise. When image eclipses art, a familiar pattern emerges: the world rushes to appropriate that image, reproducing it endlessly across magazines, billboards, and screens, stripping it of depth while amplifying its reach.

With Bardot’s passing, one might hope, perhaps naïvely, that it also marks the waning of the extremist rhetoric she helped normalize. What remains is a paradox. She contributed, almost unwittingly, to the sexual emancipation of women in the 1960s, not through political consciousness, but through provocation and instinct. She followed the prevailing winds of scandal wherever they blew, mistaking transgression for freedom.

The reality, however, was far less romantic. Born into privilege and firmly rooted in the bourgeoisie, Bardot played the populist card throughout her life. She ultimately married into circles closely connected to Jean-Marie Le Pen, the founder of France’s far-right National Front, cementing a political alignment that shocked many and confirmed the suspicions of others.

The uncritical will mourn the loss of a “people’s star,” clinging to faded images of youth and rebellion. Others will remain unmoved, seeing in Bardot not a fallen goddess, but a cautionary tale—one that forces France to confront the dangerous ease with which fame, populism, and extremism can merge when image is mistaken for meaning, and provocation for courage.

By Thierry De Clemensat

Member, Jazz Journalists Association

Editor-in-Chief, Bayou Blue Radio

U.S. Correspondent – Paris-Move / ABS Magazine